26 September 2006

"The Hungry Mile" immortalised

NSW Premier Morris Iemma today announced that Hickson Road in Sydney

will be re-named The Hungry Mile in honour of maritime workers and their

struggles during the Great Depression.

The Hungry Mile will now take its rightul place on the map of Sydney where

it will live forever as a permanent reminder of this area's heritage and the

contribution made by maritime workers," Mr Iemma said.

The Hungry Mile And ‘Maritime Invisibility’

by Rowan Cahill

When Governor Arthur Phillip began Britain’s conquest and development of Australia in 1788, he selected Sydney Cove, part of the largest natural harbour in the world for his base of operations, rather than the vulnerable, exposed, less inviting Botany Bay noted years previously by Captain James Cook.

Strategically it was obvious from the outset; the colony of New South Wales was dependent directly or indirectly on shipping, seafarers, and increasingly as time went on, shore based maritime workers (initially this work was done by convict labour). So it was for the future development of Australia, and so it remains.

The majority of exports and imports that sustain and nourish this island continent are maritime reliant. No ships, no seafarers, no maritime workers, no ports, no Australia as we know it; as simple as that. Maritime workers have contributed significantly to the development of this nation and its wealth, and continue to do so.

Sydney is a Port City, a city built around, and owing its origin to, a port. The streetscape of the Central Business District retains skeletal evidence of this, with backbone roads running inland from the former maritime hub of Circular Quay to what were general access and distribution routes, with rib roads linking the harbour’s bays and once thriving, bustling, crowded areas of wharfage, finger piers, warehouses, the myriad of premises involved in maritime trade and commerce, and crowded communities of maritime workers, who, by necessity, had to live near their workplaces.

A long, ongoing, process of mechanisation after World War 2, dramatically

changed and helped improve working conditions at sea and ashore. Until

then, however, maritime work was labour intensive, working conditions

were primitive, often harsh and unhygenic, the work physically demanding.

Large numbers of workers were required to crew ships, to load and unload

them, to repair and maintain them.

A long, ongoing, process of mechanisation after World War 2, dramatically

changed and helped improve working conditions at sea and ashore. Until

then, however, maritime work was labour intensive, working conditions

were primitive, often harsh and unhygenic, the work physically demanding.

Large numbers of workers were required to crew ships, to load and unload

them, to repair and maintain them.

It was unromantic, unsung work involving the exploitation of the human body to the extent that exhaustion, death, injury, often crippling, and bodily breakdown (e.g. respiratory diseases were abundant, along with arthritis, hernias), were not uncommon. The sea took its toll as well, even in the modern period after steam and diesel power had replaced the age-old, often dangerous and injury causing, sail technology. The twentieth century abounds with merchant marine casualties off the Australian coast.

While maritime workers generated vast profits for employers and investors, they were poorly paid; maritime workers tended to be cut out of the equation. As historian Michael Cannon has written about Australian shipowners in his book Life in the Cities (1975), “Nowhere in the psychology of these self-made men was there any place for the idea that lower-class families should share in the increased wealth of the nation”.

Confronting this attitude and contesting the power relationship involved, with a view to improving their working conditions, maritime workers variously began organizing trade unions during the early 1870s in many of the ports that dotted the Australian coast. By 1902 the two largest sectors of the maritime workforce, the seamen and the wharf labourers (wharfies), had established their own national trade union organisations, the Seamen’s Union of Australia (SUA) and Waterside Workers’ Federation (WWF). Over the course of the century these unions successfully improved the wages and conditions of their members, and in 1993 amalgamated to form the Maritime Union of Australia (MUA).

Maritime workers and their unions have long been an integral and visible part of the life of Sydney, until technological change gradually shifted port activity to Botany Bay during the 1970s onwards, and Darling Harbour and the Rocks were gentrified in pursuit of the tourist dollar. Until then, maritime workplaces on the city foreshores were part of the Sydney cityscape, as were the communities of Woolloomooloo and The Rocks where many maritime workers and their families lived in close knit communities during the nineteenth and well into the twentieth centuries.

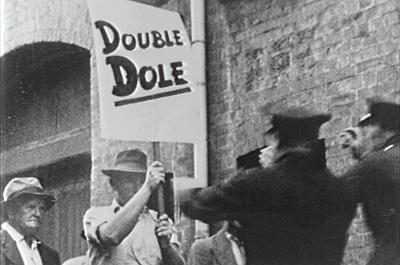

In political campaigns, protests and demonstrations, especially during

the tumultuous Cold War days of the 1950s and 1960s, large contingents

of wharfies and seamen were dramatically, theatrically, present, identifiably

so in large numbers, with union banners and placards. For much of the

twentieth century, Sydney’s maritime unions provided staple fare

for a mainly hostile media, and Sydney based national maritime union

leaders like Jim (Big Jim) Healy (WWF General Secretary, 1937–1961)

and E V Elliott ( SUA Federal Secretary, 1941–1978) were well known

public figures in their day, variously loved, respected, and reviled.

In political campaigns, protests and demonstrations, especially during

the tumultuous Cold War days of the 1950s and 1960s, large contingents

of wharfies and seamen were dramatically, theatrically, present, identifiably

so in large numbers, with union banners and placards. For much of the

twentieth century, Sydney’s maritime unions provided staple fare

for a mainly hostile media, and Sydney based national maritime union

leaders like Jim (Big Jim) Healy (WWF General Secretary, 1937–1961)

and E V Elliott ( SUA Federal Secretary, 1941–1978) were well known

public figures in their day, variously loved, respected, and reviled.

Modern technology changed the nature of maritime work, and greatly reduced the number of people employed in the maritime industry; the process continues today. A major result of this is that Sydney maritime workers are not as numerous or as visible as they once were. Technology has changed too the nature of the waterfront; maritime workplaces, once on full view to the public, are now locked behind security and safety fencing, much of the manual labour of former times eliminated by containers, large cranes, and vehicles.

In a sense the maritime worker has disappeared from Sydney as a cityscape, and in 2003 the State government of NSW announced its determination to eventually end Sydney’s role as a working port, thus freeing up foreshore land for development. Despite this ‘disappearance’, organized maritime workers still have significant political and industrial clout, something the anti-union government of Prime Minister John Howard learned during the bitter confrontation with the MUA over waterfront reform in 1998, now known as the ‘War on the Waterfront’.

But there is another sort of invisibility regarding maritime workers; as maritime historian Frank Broeze wrote in his book Island Nation (1998), maritime workers

have often been repressed in Australia’s historiography, not least because

the militant wharfies and seamen who helped tame distance were living proof

that Australia was not the country of conflict-free consensus that conservative

orthodoxy preached for so long.

A Sydney site that challenges this invisibility is the ‘Hungry Mile’, the name maritime workers gave to what was the mile of wharves between Darling Harbour and Miller’s Point, today a mix of pleasure palaces, tourist venues, and remnant maritime industrial facilities, accessed by strolling along Sussex Street and Hickson Road. In its day it was a political and industrial site that has claims to being the engineroom of a great deal of the wealth of the state of NSW, and of the nation.

It was to this mile of wharves that maritime labourers in the nineteenth

century and on into the 1940s, tramped each day regardless of the weather

to find casual, low paid work, because that was the nature of waterfront

work in those days, meaning you had to live nearby to be on hand whenever

work became available, in whatever lodgings you could afford and arrange,

rented premises, shared housing, rooming houses, sublet rooms…..

It was to this mile of wharves that maritime labourers in the nineteenth

century and on into the 1940s, tramped each day regardless of the weather

to find casual, low paid work, because that was the nature of waterfront

work in those days, meaning you had to live nearby to be on hand whenever

work became available, in whatever lodgings you could afford and arrange,

rented premises, shared housing, rooming houses, sublet rooms…..

The notorious ‘bull’ system prevailed, until a combination of factors including determined union campaigning and the wartime need by the Commonwealth Labor government to regularize manpower in an essential industry, ended the system during World War 2. The bull system pitted worker against worker, at times violently. For many labourers it was a despised, humiliating, demeaning experience. As historian Margot Beasley explains in her book Wharfies (1996):

Under this system, men assembled in a public place to be chosen for the

day’s work by foremen or stevedoring agents of the shipping companies.

Favourites for work were the “bulls”, men of such physical strength they

work longer and harder than others. Such a system also favoured compliant

and docile workers and facilitated discrimination against militant or

troublesome men who might agitate for improved conditions.

Bribery for work was another result.

For many maritime workers the Hungry Mile and their associated experiences, tramping for employment from pickup to pickup regardless of weather, being sized up by employers’ agents, scrutinised, selected, rejected, the daily routine, the competition between individuals and between gangs of workers, the angst, the uncertainty, the corruption, resulting senses of injustice, of being demeaned, victimised, came to represent the essence of capitalism, and helped shape the direction and colour of their politics, and their relationship with employers. For generations of maritime workers, the Hungry Mile lit the fires of social justice in their bellies.

During the 1930s, radical poet Ernest Antony (1894-1960) put it this way in his legendary poem “The Hungry Mile”:

They tramp there in their legions on the mornings dark and cold

To beg the right to slave for bread from Sydney's lords of gold;

They toil and sweat in slavery, 'twould make the devil smile,

To see the Sydney wharfies tramping down the hungry mile.

On ships from all the seas they toil, that others of their kind,

May never know the pinch of want nor feel the misery blind;

That makes the live, of men a hell in those conditions vile;

That are the hopeless lot of those who tramp the hungry mile.

The slaves of men who know no thought of anything but gain,

Who wring their brutal profits from the blood and sweat and pain

Of all the disinherited that slave arid starve the while,

Upon the ships beside the wharves along the hungry mile.

But every stroke of that grim lash that sears the souls of men

With interest due from years gone by, shall be paid back again

To those who drive these wretched slaves to build the golden pile,

And blood shall blot the memory out – of Sydney's hungry mile.

The day will come, aye, come it must, when these same slaves shall rise,

And through the revolution's smoke, ascending to the skies,

The master's, face shall show the fear he hides, behind his smile,

Of these his slaves, who on that day shall storm the hungry mile.

And when the world grows wiser and all men at last are free,

When none shall feel the hunger nor tramp in misery

To beg the right to slave for bread, the children then may smile.

At those strange tales they tell of what was once the hungry mile.

Largely self educated, Antony was no stranger to hardship; he led a nomadic working life, always part of the trade union movement, variously labouring in rural industries, mines, the railways, and on the waterfronts of Newcastle, Port Kembla, and tramped the Hungry Mile in 1930. Merv Lilley, a former miner, seaman, and long time writer, poet, refers to this poem, and its power to move people politically, in his fictionalised autobiography The Channels (2001), recalling the Cold War years of the 1950s:

"Jack Long had heard fragments of this poem around Queensland ports, bars,

as an itinerant toiler; it may have been those fragments that at last drew him

toward the centre of things. There was no such thing as a bad poem about

working conditions, there were ironic poems that fought to scan and rhyme,

and they were poems that spoke about men's lives when no other words of

praise and sympathy and recognition were around to reflect their lives, if not

on stone, then on words".

Alongside its industrial and political roles, the Hungry Mile was an

urban area, a site of working class domesticity. Before the post-1945

rapid expansion of suburban Sydney, before the end of the bull system,

generations of maritime workers and their families lived within the geography

of the Hungry Mile, so close they were part of it. From the government

built flats for the families of maritime workers on Observatory Hill,

to the long rows of tenements in Kent Street, to the rooming houses on

Sussex Street, one of which in 1907 was packing in 200 maritime labourers,

a community developed. Historian Winnifred Mitchell has described the

lives of families within this community as being “like those in

a coal-mining village”. It was in this urban geography close to

the Hungry Mile that families lived, children were raised, and thousands

of future workers learned about the world, how they related to it, and

how it was to be faced.

Alongside its industrial and political roles, the Hungry Mile was an

urban area, a site of working class domesticity. Before the post-1945

rapid expansion of suburban Sydney, before the end of the bull system,

generations of maritime workers and their families lived within the geography

of the Hungry Mile, so close they were part of it. From the government

built flats for the families of maritime workers on Observatory Hill,

to the long rows of tenements in Kent Street, to the rooming houses on

Sussex Street, one of which in 1907 was packing in 200 maritime labourers,

a community developed. Historian Winnifred Mitchell has described the

lives of families within this community as being “like those in

a coal-mining village”. It was in this urban geography close to

the Hungry Mile that families lived, children were raised, and thousands

of future workers learned about the world, how they related to it, and

how it was to be faced.

Rowan Cahill is a historian and writer with a background in teaching, journalism, and agricultural labouring. He has worked for the trade union movement as a publicist and rank and file activist, and is President of the Sydney Branch of the Australian Society for the Study of Labour History.

This article was commisioned by the MUA as a part of their

successful Hungry Mile campaign.